Simple and Fast Consensus with Zug

The Casper node was designed with a pluggable consensus protocol in mind. So far the only choice was Highway. Casper 2.0.0 has added Zug, a much simpler consensus protocol.

The Zug protocol requires that at most one-third of the validator weight could be attributed to faulty validators. It also assumes that there exists an upper bound for the network delay, which is the duration for a correct validator to deliver a message. The value of the upper bound may be unknown, but it exists. Under these conditions, all correct nodes will reach agreement on a chain of finalized blocks.

Of course, all nodes in a network have to run the same protocol to work together, but when starting a new network or upgrading an existing one, either Highway or Zug can now be selected as the consensus_protocol in the chainspec file. The Casper Mainnet will switch to Zug.

How Zug Works

In every round, the designated leader can sign a proposal message to suggest a block. The proposal also points to an earlier round in which the parent block was proposed.

Each validator then signs an echo message with the proposal's hash. Correct validators only sign one echo per round, so at most one proposal can get echo messages signed by a quorum. A quorum is a set of validators whose total weight is greater than (n + f) / 2, where n is the total weight of all validators and f is the maximum allowed total weight of faulty validators. Thus, any two quorums always have a correct validator in common. As long as n > 3f, the correct validators will constitute a quorum since (n + f) / 2 < n - f.

The proposal is accepted if there is a quorum and some other conditions are met (see below). Now, the next round's leader can make a new proposal that uses this proposal as a parent.

Each validator observing the proposal in time signs a Vote(true) message. If validators time out while waiting, they sign Vote(false) message instead. If a quorum signs true, the round is committed and the proposal and all its ancestors are finalized. If a quorum signs false, the round is skippable, meaning that the next round's leader can propose a block with a parent from an earlier round. Correct validators only sign either true or false, so a round can be either committed or skippable, but not both.

If there is no accepted proposal, all correct validators will eventually vote false, so the round becomes skippable. This is what makes the protocol live. The next leader will eventually be allowed to make a proposal because either there is an accepted proposal that can be the parent, or the round will eventually be skippable, and an earlier round's proposal can be used as a parent. If the timeout is long enough, the correct proposers' blocks will usually get finalized.

For a proposal to be accepted, the parent proposal must also be accepted, and all rounds between the parent and the current round must be skippable. This is what makes the protocol safe. If two rounds are committed, their proposals must be ancestors of each other because they are not skippable. Thus, the protocol cannot finalize two conflicting blocks.

Of course, there is also a first block. Whenever all earlier rounds are skippable (particularly the first round), the leader may propose a block with no parent.

Every new signed message is optimistically sent directly to all peers. We want to guarantee that it is eventually seen by all validators, even if they are not fully connected. This is achieved via a pull-based randomized gossip mechanism, where a SyncRequest message containing information about a random part of the local protocol state is periodically sent to a random peer. The peer compares that to its local state and responds with all the signed messages that it has recorded.

The Zug protocol can be summarized as follows:

- In every round, the round leader proposes a new block,

B. - Every validator creates and broadcasts an echo message, with a signature of

B. - When a suitable block

Bhas received echoes from 67% of the validators:- The next round begins. The next leader can propose a child of

B. - Every validator signs and broadcasts a vote message, voting

yes.

- The next round begins. The next leader can propose a child of

- If this does not happen before a timeout, the validators vote

noinstead.- If there are

novotes from 67%, the next round begins, too. The next leader can propose a child from an earlier block and skip this round.

- If there are

- If there are

yesvotes from 67%,Bis finalized and gets executed, together with all its ancestors. (Usually, the next round has already started at this point.)

Notice that proposals, votes, and echoes are broadcast, so if one correct node receives a message, all nodes will eventually receive it. An honest validator sends only one echo or vote per round. So, unless 34% of validators double-sign, at most one block per round gets 67% echoes, and no finalized block can ever be skipped, ensuring safety. As long as there are 67% of echoes for a proposal, the next round begins and Zug doesn't get stuck. If there are not, everyone votes no, and the next round also begins.

Expand to see a simple example

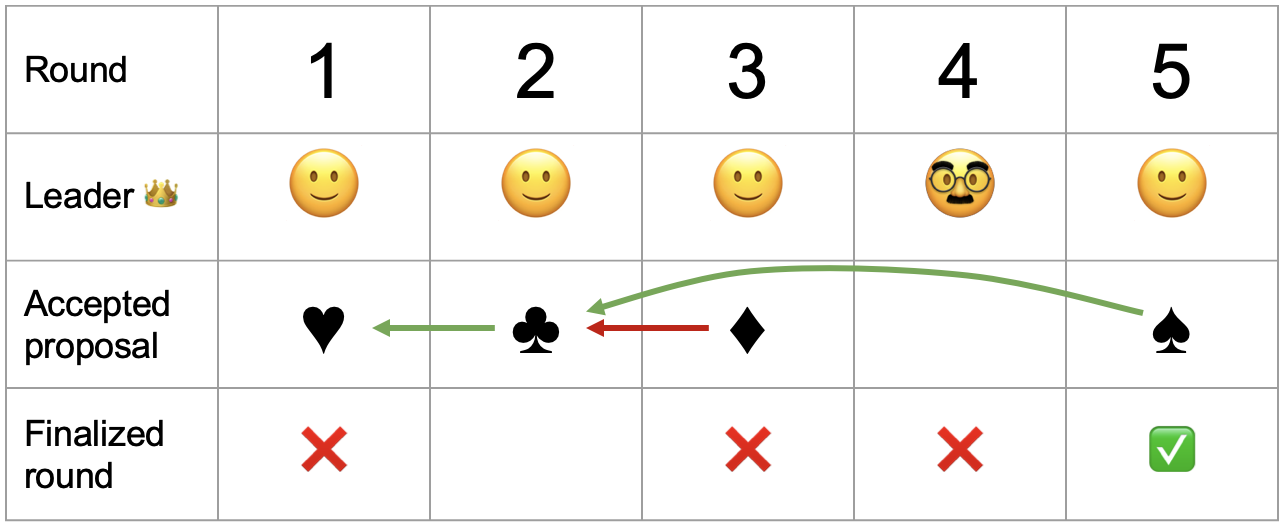

Let's review a simple scenario demonstrating the Zug consensus. The example shows five rounds with a different leader and nodes voting on a card suit. The bottom row indicates whether or not the round was finalized. Notice that round 5 was the first finalized round.

In round 1, we had a leader who proposed ♥, but was slow, so the other nodes timed out and voted no. The first round had a proposal and was skippable, but nothing was finalized.

In round 2, the second proposer saw ♥ and proposed ♣ as a child of ♥. Some nodes voted yes, and some timed out and voted no. So, round 2 will never output anything because there wasn't a decision.

In round 3, the leader proposed ♦ as a child of ♣. Assuming the leader was still too slow, everyone voted no, and round 3 became skippable even though it had a proposal.

In round 4, the proposer might have crashed or been malicious, so everyone timed out and voted no.

In round 5, the leader didn't see the ♦ proposal from round 3 but saw the no decision. So, from their perspective, rounds 3 and 4 were skippable and had no proposals. Thus, the leader in round 5 proposed ♠ as a child of ♣. Notice that the algorithm encountered a fork. Regardless, everyone voted yes, and round 5 was finalized. I.e., at that moment, ♥, ♣, and ♠ all become finalized and executed in that order. As a result, every future proposer needs to propose children of this round.

Important Notes:

Even proposals from rounds with a quorum of no votes can become finalized indirectly.

If a round is neither finalized nor skippable, the round will likely be finalized at some point in the future. When one-third of the network's weight votes yes, a proposal with a quorum of echoes is formed. Consequently, all other honest nodes will eventually see this quorum of echoes and the accepted proposal, which will serve as a parent in future rounds.

Nodes vote yes when they have a quorum of echoes, and all the ancestors of that proposal have a quorum of echoes. Also, those ancestors have a quorum of echoes, and the rounds with no ancestors all have a quorum of no votes (being skippable).

The algorithm will always produce a result in at least one of the Accepted proposal or Finalized round rows. If a proposal doesn't get accepted in a round, everyone times out and votes no. Otherwise, a proposal is visible to someone with a quorum of votes and will eventually be visible to everyone.

Some Advantages of Zug

- Apart from the leader, who has to send the proposed block, each validator node broadcasts only two tiny messages in each round, making the communication overhead very small.

- Unlike in Highway and Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT), and similar to pipelined protocols like HotStuff, only one round of messages (the echoes) is needed for the next leader to propose a block, reducing the delay between a block and its child.

- But unlike HotStuff, Zug can finalize a block without waiting for its child or grandchild. And, unlike Highway, it does so without waiting for any timeout. Even if a network is configured to produce only one block per minute, every block gets finalized within seconds, as fast as the network connections allow.

- Zug's technical description is more flexible than Highway's, giving us a family of related, correct implementations from which to choose.

Comparison with Highway

Unlike Highway, Zug does not use a communication history DAG. Highway sends larger messages due to citing and is slower. Zug does not have any notion of citing units, as does Highway, and relies on exchanging signed messages. On the other hand, Highway allows for more fine-grained block rewards.

With Zug, finality happens after nodes constituting two-thirds of the network's total weight vote true for a round in which the block was proposed or a later round that has this one as an ancestor. Highways' criterion for detecting finality is the presence of a pattern of messages called a Summit. Summits preserve the advantage of tunable fault tolerance while being detected in polynomial time. Both ways of detecting finality are improvements over previous CBC Casper finality criteria, which were more difficult to attain and computationally more expensive to detect.

Highway and Zug offer flexibility in terms of fault tolerance thresholds. Highway allows different clients to follow the protocol with varying thresholds, each with its own balance between security and latency. However, if a sufficient number of validators are online, Zug demonstrates lower latency than Highway at any threshold. This is because Zug does not have predefined, rigid values for the round length, and its design allows the network to adapt to actual delays. If delays occur, block times may vary. Otherwise, blocks should appear as soon as they are finalized. Highway has a defined minimum round length, and the round lengths have to be powers of two times that minimum. Zug has a defined minimum round length, but a round can finish anytime as soon as enough messages are successfully exchanged. So, with Zug, there is no need to wait for a power of two times the minimum if the actual time falls somewhere between.

Highway is a much more complicated protocol than Zug. Implementing it takes more than twice as many lines of code. Also, Highway's proof of correctness has proved more difficult to verify than Zug's. Zug will make it easier for third parties to create compatible node software that works with the Casper node.

Using Zug consensus and smaller messages, the network could scale to a larger number of validators.

Block Rewards

Using a DAG in Highway makes fine-grained information about the validators' behavior available temporarily in the protocol state, so block rewards can be tuned to incentivize full participation in the consensus protocol. However, this does not apply at the end of each era. Any message sent after the era's last block was proposed cannot be taken into account, even though these messages are still needed to finalize that block. And this granularity comes at a cost: Highway messages are relatively big.

The current system does not reward finality signatures, which are arguably the most important outcome. The signatures are the user-visible proof, signed by the validators, that an executed block is correct.

In Zug, messages are much smaller, so a smaller incentive is needed to send them.

Casper 2.0.0 will distribute a configurable fraction of the seigniorage as a reward for finality signatures and the rest as a simple reward for each block, both proportionally to the validators' stakes.

This new reward system is simpler, fairer, predictable, and transparent. It will give equal weight to all blocks (including at the end of an era), but it will not take into account every single consensus message.

Read the Paper

Here, we describe Zug, an implementation of the ideas from our paper From Weakly-terminating Binary Agreement and Reliable Broadcast to Atomic Broadcast. The paper, however, contains a much more general algorithm parameterized by the two subprotocols named in the title: Reliable Broadcast and Weakly-terminating Binary Agreement. In our specialization of this algorithm made for the Casper blockchain, the echo messages are used by our Reliable Broadcast implementation, and the vote messages are used by our Weakly-terminating Binary Agreement implementation.